Taek-“Win”-do

Junior Shares Her Experience in Competitive Taekwondo

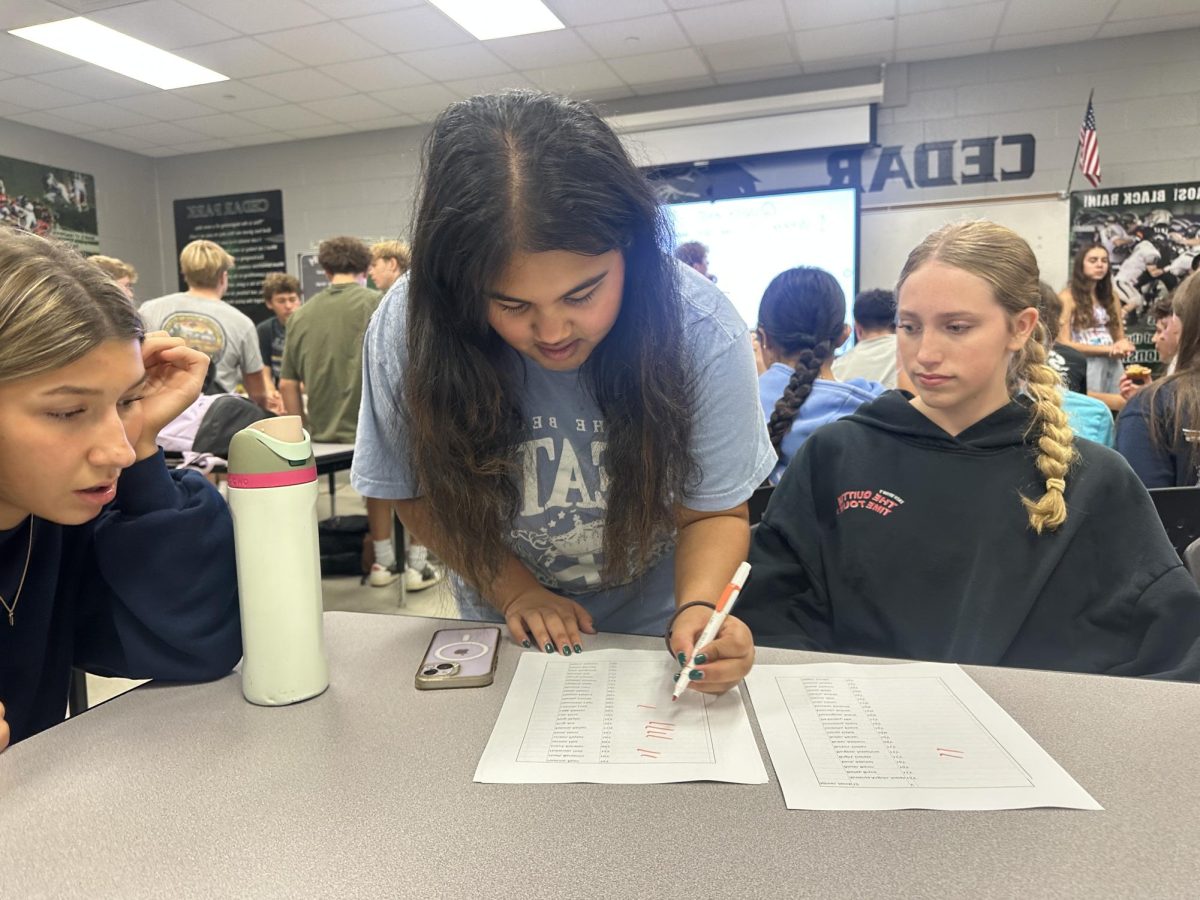

Posing with her USA gold medal, junior Aahana Mulchandani holds the certificate verifying her place on Team USA Taekwondo team. Mulchandani will represent the team this April in the Dominican Republic for the Pan American Taekwondo Championships. “I’m really excited to go [to the Dominican Republic because] I’ve never been there,” Mulchandani said. “I’m a little bit nervous too, [but] I feel very honored to [compete] because I fought so hard [to make the team]. I have a very [good] shot [at winning] if I do my best. My coach would probably kill me if I didn’t.” (Photo Courtesy of Aahana Mulchandani)

March 22, 2023

Everything is silent. She can’t hear the clapping crowd’s whistles, the voices speaking to her or feel the rough pats on her back. Frantically whipping her head around, she looks for the one face that can tell her what is going on. Vivid colors, ponytails and bodies swarm her vision, faces of people popping in and out of sight, none of which are the one she’s looking for. She pushes through another cluster of people and only then does she spot the face, but it’s running toward her at full speed. When her coach gets to her, she has only two words.

“You won.”

Eleventh grader Aahana Mulchandani will represent Team USA this April at the Pan American Taekwondo Championships in the Dominican Republic. Mulchandani is Team USA’s team member for the junior female individual poomsae position. She has trained in taekwondo since she was 6 years old, and said she never wants to stop competing in the sport.

“Taekwondo is a Korean martial art,” Mulchandani said. “There’s two different sides to taekwondo; there’s poomsae and there’s sparring. Sparring is actual combat. I do poomsae, which is the artistic, pattern-based [type of taekwondo]. In order for you to do legitimate taekwondo, you have to know both, and I did both very intensively, but I only [compete in] poomsae now.”

The different levels of competition within competitive taekwondo are local, state, regional, national and international. USA Taekwondo is a branch of Team USA, and to make the team you must meet certain requirements, such as having a USA Team membership and winning first place in the national team trials to earn a spot on the team.

“There are two different rounds [at the team trials]; one of them is the qualification round,” Mulchandani said. “You have to do three forms, [which are] like [taekwondo] patterns, [and the judges evaluate your performance on the forms]. If you win, you move onto the elimination round, and that’s where you have to face off against [the other] top athletes. Whoever wins in the elimination round is the national team member.”

Mulchandani’s taekwondo journey began in California, where she lived before she moved to Texas during the pandemic. She was first introduced to the martial art when she was watching TV one day.

“When I was around three, I saw a PBS interview, and it was of this really revered lady; she could do backflips, she could do so many things,” Mulchandani said. “She was an actual badass. I thought she was the coolest person ever, and my mom [told me the woman did] taekwondo. [I thought that was cool], and then I kind of forgot about it [for a while].”

A few years later, Mulchandani told her mother she wanted to learn how to fight. Her mom signed her up for taekwondo class at an elite-team school called Taekwon Kids, and she started training.

“I was around 6 or 7 years old when I joined [the] elite team,” Mulchandani said. “I was a founding member of that team, [but] I ended up moving schools. I [then] joined this team called Eagles, [which was] a very intensive poomsae team. They had several people on the national team at the time [for taekwondo].”

While training with Eagles, Mulchandani started to have a problem with her mobility in practice. Her flexibility was declining, and she was experiencing a lot of pain when she would stretch or do a kick.

“When I was super young, I had a lot of flexibility,” Mulchandani said. “But when I started growing, I ended up having an issue where I lost my flexibility. I went to an orthopedic surgeon, and he diagnose[d me] with hip impingement. [That means] I don’t have a lot of hip room; my socket [where my leg and hip connect] is really tiny. Every time I lifted my leg, it would cause me a lot of pain.”

The doctors told Mulchandani she was too young to have surgery on her hips, and when they could operate the recovery time would be over a year. Two orthopedic surgeons advised her to give up all of taekwondo because it would be a risk to her health.

“The [surgeons] said [I was] probably not going to be able to walk after 30 if [I stayed in taekwondo],” Mulchandani said. “But I [didn’t] want to give [taekwondo] up, because it’s something I'[d] done for years. And there’s so much I [hadn’t] done yet. So I just kept pushing forward. I [went] to physical therapy, I got chiropractors, I did so much intensive care on my hips to preserve [my physical condition] to the best of my ability.”

When she turned 12 years old, Mulchandani made the national taekwondo team as the cadet female poomsae competitor, and was able to travel to Taipei with Team USA. Mulchandani said that around this time was when she began to have a lot of self confidence issues when she practiced taekwondo because of her hips and the restricted mobility they put on her.

“I couldn’t kick the same way everyone did, I couldn’t do certain things that everyone else could,” Mulchandani said. “That ended up making me lose [at competitions] a lot. I be[came] what used to be the top [athlete] to just a semi-final player. I couldn’t break into finals at all. It was so difficult for me mentally because I just ke[pt] losing and losing and losing.”

Mulchandani had just turned 14 years old when the pandemic hit and she and her mom moved to Texas. After she didn’t make the national team that year, she decided to take a year-long break from taekwondo.

“I didn’t compete at all for the entire year [of 2020],” Mulchandani said. “[Then] at the end of the year, my mom flew me out to [Los Angeles], where my [taekwondo] team was based. I train[ed] really intensively for weeks just trying to get back my physical condition. [Since] I didn’t do anything for several months, I lost all my muscle and gained weight. I grind[ed] it out, and hop[ed] that maybe my physical condition would come back. Luckily, it did.”

After getting back into taekwondo, Mulchandani competed in the U.S. Open, a major taekwondo competition that was virtual that year. She won third at the competition, and said placing bronze came as a surprise for her since she had taken such a long break.

“I won third, [and] it was a big moment,” Mulchandani said. “But then I kind of plateaued and started losing again, [even though] I was doing a lot better this time. I kept my spirits high [and told myself] I [wasn’t] expecting much [anyway].”

At each of her taekwondo competitions, Mulchandani was competing in the individual, pair and team divisions, which are often all on the same day, so her hips were suffering from the strain they were put under.

“My hips were having a field day [at every competition] trying to work through all [the forms],” Mulchandani said. “I [had to] conserve [myself and] prepare. I was very strategic with [how I managed my hip injury].”

Mulchandani’s team for the team division at taekwondo events consisted of her and two older girls, one of whom didn’t agree with the formation the girls performed in during competitions.

“[That one girl] had an issue with me even though I didn’t do anything wrong,” Mulchandani said. “We got into a lot of conflict to the point where I could not take it anymore. I ended up leaving Eagles [Taekwondo team]. It was one of the most horrible and depressing moments I’ve ever had, because this was a team that I practically grew up with. I was really upset that I had to leave.”

For a few months, Mulchandani was competing without a team to represent. During this time she made the Texas State Taekwondo team for junior female individual and won the title of Texas State Champion while her mom looked around Texas for teams she could start to train with.

“[One day my mom told] me that the same girl [I] saw on PBS when [I was] 3 [years old] was [teaching poomsae in Texas],” Mulchandani said. “I ended up going to their [facility] to train, and because I liked the environment so much, it didn’t take me very long to realize [that was] where I want[ed] to be. So I ended up joining her team, called Texas Team Forge, and that’s where I’ve been for the rest of my time, with that exact lady [from the PBS interview] as my coach. Her name is Adalis Munoz [and] I love her. I’m basically training with my idol.”

Mulchandani said the relationship she has with “Master AJ,” which is what she calls Munoz, is a very special one because of all the time they spend together and the experiences they share.

“She’s an amazing coach and I have such a personal connection to her,” Mulchandani said. “I even went to her wedding; it’s insane. I [also] really admire her story. She has been on the national team so many times, she’s also been world champion so many times. She is a legend in the poomsae community. It’s really intense, [training with Munoz], but she’s the reason I made the national team. If she didn’t put in as much effort as she did on me, and if I didn’t push hard enough, then I wouldn’t have made it this year.”

After joining Team Forge, Mulchandani found a chiropractor in Texas that had the skills to help her with her hip impingement, and said this was a pivotal point for her. She still goes to see the chiropractor to this day, usually once a week.

“[My chiropractor is] very understanding about [my] hip issues,” Mulchandani said. “He basically help[ed] me carve away all the scar tissue that built up while I was injured. [After working with him], I was able to finally kick vertical[ly]. I almost cried [when I found out I could vertical kick again], because that was something I'[d] been hoping to do for such a long time, and I was finally able to do it. I don’t think without [my chiropractor] I could have done any of this.”

Mulchandani went to nationals with Team Forge in 2021 and was able to make it to the final round with the final eight competitors, which she said was a big moment for her.

“Master AJ was like, ‘yeah, like this is awesome. Just don’t lose your cool,’” Mulchandani said. “I lost my cool and I got seventh. But that’s okay. I was just very happy at the time, and ever since I joined Team Forge I kept consistently making the top eight [at competitions]. It was amazing.”

During winter break of December 2022, Master AJ told Mulchandani there was a two-week winter camp in Dallas, and she wanted Mulchandani to go and train at it.

“[Master AJ said she was] going to turn [me] into a national champion [at the winter camp],” Mulchandani said. “So I went and trained with her for very long hours. It was from 9 a.m. to 12 p.m. and then 1 p.m. to 4 p.m. all on the same day. Sometimes I’d [also] have private lessons with her that would go for two [or] three hours each. It was a rough time, but I really enjoyed it.”

The winter camp would prepare Mulchandani for the National Taekwondo Team trials held in Tulsa, Oklahoma, on Feb. 11, which was what her and Master AJ had been working toward for months.

“[National team trials day] was a big day for me and my coach,” Mulchandani said. “[When the competition started], I ended up losing the first round of qualifications, but then I won the second round, [which] is what got me into the elimination round.”

All day, her coach wouldn’t let her see the scores she was getting on her poomsae forms to prevent Mulchandani from getting nervous. She said she could only gauge how well she did from the audience’s reaction to her performance and the T.V. screen displaying the competition times and scores, which was facing away from her.

“I did not know what was going on the entire time [at the team trials],” Mulchandani said. “My coach was running back and forth [between me and the T.V. to tell me when I was competing]. She was the control tower the whole time. It was crazy. I wasn’t allowed to look at my competitors either. It was like they put a blindfold over me, and I was just standing [around] waiting for my turn [to compete].”

After she competed in eleven rounds of poomsae taekwondo and the competition was over, Mulchandani still didn’t know how she did until her coach found her in the crowd and told her.

“It was kind of funny because I didn’t know if I [had] won or not,” Mulchandani said. “And then my coach ran [over to me, and] she’s like ‘you won.’ Immediately all I did was cry. I was just so overwhelmed. My whole team ran over from their side of the [competition] ring and they were just hugging me [and] we were all crying together. I felt so warm and happy at that moment. It was just one of the most indescribable feelings ever. And then they [called] ‘third place, second place, first place!’ And for the first time in what felt like such a long time I was the first place [winner]. I [hadn’t] felt [that] in 4 years. Everyone was clapping, crying, [and] my mom did not know what to do with herself. It was a frenzy. It was insane because I ended up winning [national team trials] by a huge margin.”

The point system for poomsae taekwondo is divided into two categories: accuracy and presentation. Presentation is usually on a six-point scale, and the accuracy is on a four-point scale. Mulchandani said very high scores are 8.0 and above out of the ten possible points competitors can receive.

“[I found out later that] my scores did not drop below an eight,” Mulchandani said. “Even in the qualification round, my score did not drop below an eight. I was 8.0 and above the entire 11 rounds, and I only lost one round. So I won 10 out of 11. It was crazy.”

Mulchandani’s scores were added up and compared to her competitors’ total scores. Her score was 65 points, and the second place winner had 64.

“I had a 1.0 gap [between my and the second place winner’s score],” Mulchandani said. “Usually [the gap is] 0.1 or 0.2. I’ve lost [competitions] by 0.01. And [my competitors were] two people who are very good athletes.”

One of Mulchandani’s younger teammates, Elle, also made the national team, and her teammate Jason made it as an alternate team member.

“We were all over the moon,” Mulchandani said. “My coach was like, ‘Let’s go get hotpot for dinner!’ We were all celebrating. I have a very good support group [now]. There’s absolutely no toxicity on [Master AJ’s] team. She’s very specific about the environment; it’s very positive and encourages growth.”

Team Forge is a smaller team, with only 15-20 members. Taekwondo teams commonly have upwards of 50 members, and at competitions or events there are hundreds of competitors present. Team Forge is getting more recognition in the taekwondo community because of three of its students making the national team.

“On Saturday I’m competing in the U.S. Open [competition] in Las Vegas, which is [a] really big [event],” Mulchandani said. “The Vietnam national team is coming, [the] Hong Kong national team is coming, Korea is coming. It’s international. I think [I’ll] do pretty well, as long as I just keep my cool. Now that I know I’m [on the] national team, there’s more of a chance I’m gonna get nervous and stressed out because there’s so much weight I’ve got to carry.”

After the U.S. Open, Mulchandani will begin preparing for the Pan American championships in the Dominican Republic this April, when she’ll represent the United States in her division for poomsae taekwondo.

“I’m really excited to go [to the Dominican Republic because] I’ve never been there,” Mulchandani said. “I’m a little bit nervous too, [but] I feel very honored to [compete] because I fought so hard [to make the team]. I have a very [good] shot [at winning] if I do my best. My coach would probably kill me if I didn’t. Honestly, that for me is the event of the year. If I win, I think I’m going to feel very confident [about] everything else. It’s going to be right before AP exams, though, so that’s going to be interesting.”

Balancing school and taekwondo can prove to be a challenge, Mulchandani said, and sometimes it’s nearly impossible. Monday and Tuesday are strength and conditioning days, Wednesday is for visiting her chiropractor, Thursday and Friday are reserved for taekwondo lessons and Saturday and Sunday are used to train all day at a facility in Dallas.

“[There’s] a lot of late nights,” Mulchandani said. “I’ll be up at 2 a.m. still finishing [classwork], I’ll be [on a] plane and working, I’ll be doing stuff at the airport, and [I’ll] even be working on an assignment while [my teammates] compet[e].”

Mulchandani said group projects are especially tricky for her to handle, and finds it’s best to try and work alone on her assignments because that’s the best thing that works for her schedule.

“It’s a lot of communication that I have to do with my teachers,” Mulchandani said. “If there’s group projects, I have to try to ask the teacher if I [can work] alone because there’s no way I can maintain contact with [any group members I’d have] while also competing. That’s why I’m also not really in a lot of clubs. I’m in NHS, [and] that’s really it, [and] it’s so difficult keeping up [good] grades.”

She has a lot of tests to constantly make up, Mulchandani said, and has to schedule time to take missed exams during DEN, before and after school. One of the worst things to deal with as a taekwondo competitor are due dates, she said.

“Especially if [I’m] traveling, it’s hard to work with deadlines,” Mulchandani said. “For example, if I’m [flying] to California, which is two hours behind, and I have assignments due at 8:15 a.m., Texas time, I have to get it in by 6 a.m., California time, for me to meet the deadline properly. My sleep schedule is very messed up. Some days I’ll go to bed reasonably early, like at nine, [but] other days I just won’t sleep.”

With a social life not on par with her classmates, Mulchandani said it can be hard to have friends from school who will appreciate her commitments to taekwondo.

“I don’t have a lot of friends [at school],” Mulchandani said. “I have [some] classmates that I regularly talk to, [and] I have a couple of good friends that I eat lunch with, but aside from that I don’t really have a social life. My coach said [some]thing [one of the first days I trained with her]. She told me [and her other students]: ‘Look around. These people are going to be your best friends. You’re not going to see the friends you have in school very much if you want to chase the same type of dream that I chase.’ I took [what she said] to heart.”

Mulchandani tries to find time to hang out with her school friends, but said she never has enough time to even catch a breath before boarding a plane to get to a competition in another state or country, or finishing a school project just in time for the deadline.

“All my free time has to be at school,” Mulchandani said. “It’s really rough balancing school and taekwondo because high school is supposed to be a time for being very social [and] getting to know yourself. I might have to miss prom this year, and maybe even senior year, because I have to go compete. It’s hard for me to make friends too. I’m not trying to say [taekwondo] is my personality, but it makes up most of my life. It’s hard to find people who will understand you, and who will understand that you’re absent and there’s complications and choices that I have to make and sacrifices that I make.”

Most people don’t know she’s a competitor on Team USA, Mulchandani said, for good reason.

“I try to keep it under wraps, in a way, because I don’t want [anyone] think[ing] I’m a gangster or something,” Mulchandani said. “When I [tell] people I do taekwondo [and I’ve been] on national television, they stay away from [me]. As long as the people who matter to me know about it, that’s what matters.”

With all the time, money, passion and grit that goes into training in taekwondo, Mulchandani said she sometimes thinks over her life choices that have taken her to where she is today.

“There are moments where I question [my commitment to taekwondo],” Mulchandani said. “What would my life be like if I had made certain decisions? What would my life be like if I didn’t chase a sport this intensive? But then I always realize how lucky I am to be able to do all of this. I’ve [trained this hard] because I love the sport. I can’t say I regret it. It’s been such a journey for me as a person too, because there are so many values that you learn from the sport, like respect and self-control. I guess it’s a lot of mental conditioning, too, which is something that I don’t think you can ever put a price tag on. And there’s so much friendship and sportsmanship that you gain. Honestly, I get to travel the world.”

Her hip impingement surgery would be available to her when she turns 20 years old, but Muchandani said the effects the surgery would have on her aren’t worth the time and pain it would require.

“I want to continue [taekwondo] forever if I can,” Mulchandani said. “If I do end up retiring, I want to be a coach. It’s [fun] to watch [beginner students] grow up, and it’s humbling because you realize [you were] exactly like them at one point in life. [Taekwondo] is mentally taxing; some days feel very depressed [and] other days feel on top of the world. Normally, [I’m] super emotionally and physically exhausted, [but] there’s so much that I’ve done and when I look back at it now, it’s like I defied orthopedic surgeons. I’ve [done] what they said wasn’t possible. Now I’m here. This is like a whole new chapter of life for me.”

![Senior Jett Mckinney stores all the clothes in his own room, with half of it stored in his closet along with his personal clothes, and the rest taking up space in his room.

“There’s been times [when] there’s so much clothing stored here and it gets overwhelming, so I end up having to sleep somewhere else in the house,” Mckinney said.](https://cphswolfpack.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/DSC_0951-1200x800.jpg)

![Broadcast, yearbook and newspaper combined for 66 Interscholastic League Press Conference awards this year. Yearbook won 43, newspaper won 14 and broadcast took home nine. “I think [the ILPC awards] are a great way to give the kids some acknowledgement for all of their hard work,” newspaper and yearbook adviser Paige Hert said. “They typically spend the year covering everyone else’s big moments, so it’s really cool for them to be celebrated so many times and in so many different ways.”](https://cphswolfpack.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/edited-ILPC.jpg)

![Looking down at his racket, junior Hasun Nguyen hits the green tennis ball. Hasun has played tennis since he was 9 years old, and he is on the varsity team. "I feel like it’s not really appreciated in America as much, but [tennis] is a really competitive and mentally challenging sport,” Nguyen said. “I’m really level-headed and can keep my cool during a match, and that helps me play a bit better under pressure.” Photo by Kyra Cox](https://cphswolfpack.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/hasun.jpg)

![Bringing her arm over her head and taking a quick breath, junior Lauren Lucas swims the final laps of the 500 freestyle at the regionals swimming competition on date. Lucas broke the school’s 18-year-old record for the 500 freestyle at regionals and again at state with a time of 4:58.63. “I’d had my eye on that 500 record since my freshman year, so I was really excited to see if I could get it at regionals or districts,” Lucas said. “ State is always a really fun experience and medaling for the first time was really great. It was a very very tight race, [so] I was a bit surprised [that I medaled]. [There were] a lot of fast girls at the meet in general, [and] it was like a dogfight back and forth, back and forth.” Photo by Kaydence Wilkinson](https://cphswolfpack.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Kaydence-2.7-23-edit-2.jpg)

![As her hair blows in the wind, senior Brianna Grandow runs the varsity girls 5K at the cross country district meet last Thursday. Grandow finished fourth in the event and led the varsity girls to regionals with a third place placement as a team. “I’m very excited [to go to regionals],” Grandow said. “I’m excited to race in Corpus Christi, and we get to go to the beach, so that’s really awesome.” Photo by Addison Bruce](https://cphswolfpack.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/brianna.jpg)

![Posing with her USA gold medal, junior Aahana Mulchandani holds the certificate verifying her place on Team USA Taekwondo team. Mulchandani will represent the team this April in the Dominican Republic for the Pan American Taekwondo Championships. “I'm really excited to go [to the Dominican Republic because] I've never been there,” Mulchandani said. “I'm a little bit nervous too, [but] I feel very honored to [compete] because I fought so hard [to make the team]. I have a very [good] shot [at winning] if I do my best. My coach would probably kill me if I didn’t.” (Photo Courtesy of Aahana Mulchandani)](https://cphswolfpack.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/unnamed-600x900.jpg)

![Holding a microphone, baseball booster club president Chris Cuevas announces the beginning of the annual cornhole tournament. The event has been held for the past two years and is designed to raise money for the baseball program in a fun way. “We’re a baseball team, so people love to compete,” Cuevas said. “So we figured we better do something that gets [their] attention. They want to compete. It’s not a hard sport to do, and we have all different [skill] levels [of participants].” Photo by Henry Mueller](https://cphswolfpack.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/Henry-715-1200x900.jpg)