Are You Cheating on Me?

Teaches Speak About Cheating, How They Are Combating It

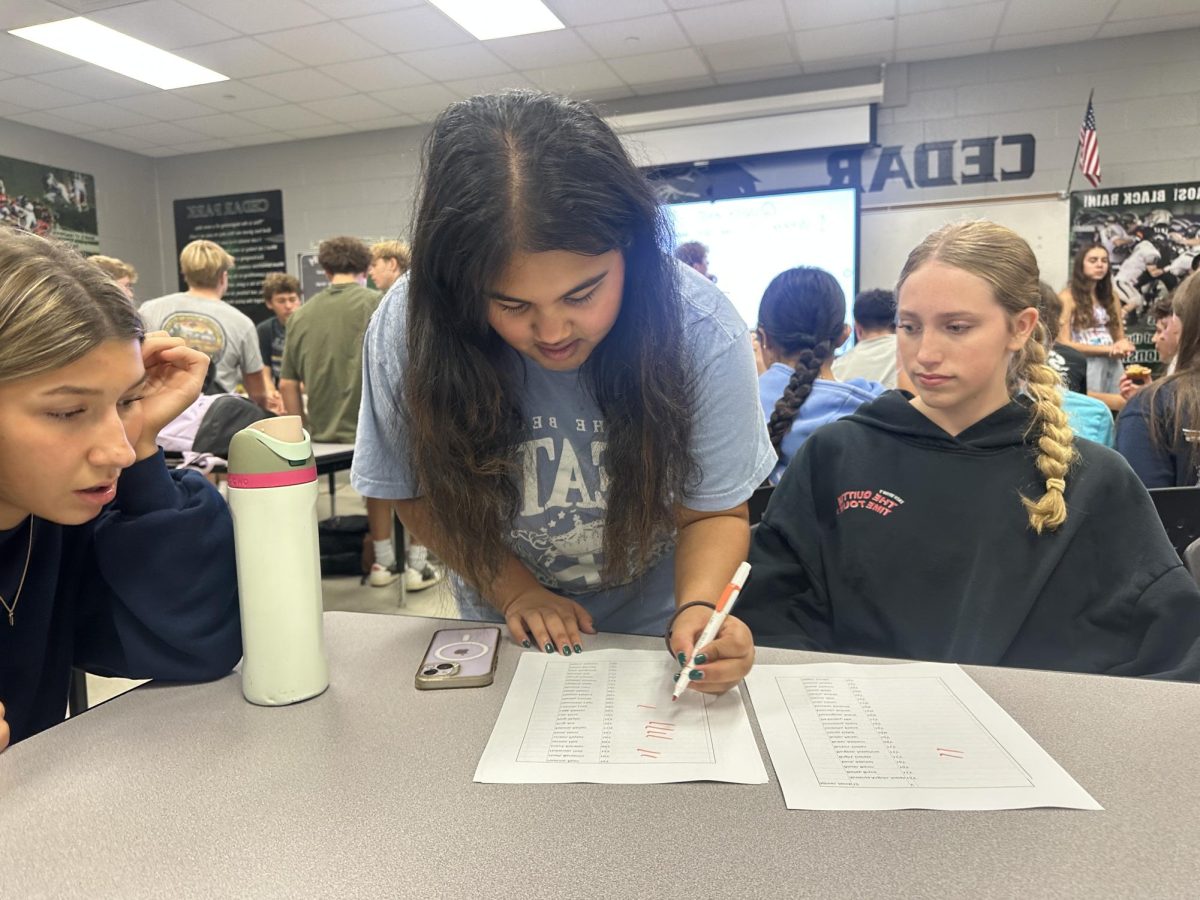

Photo Courtesy of Ruchi Sankolli

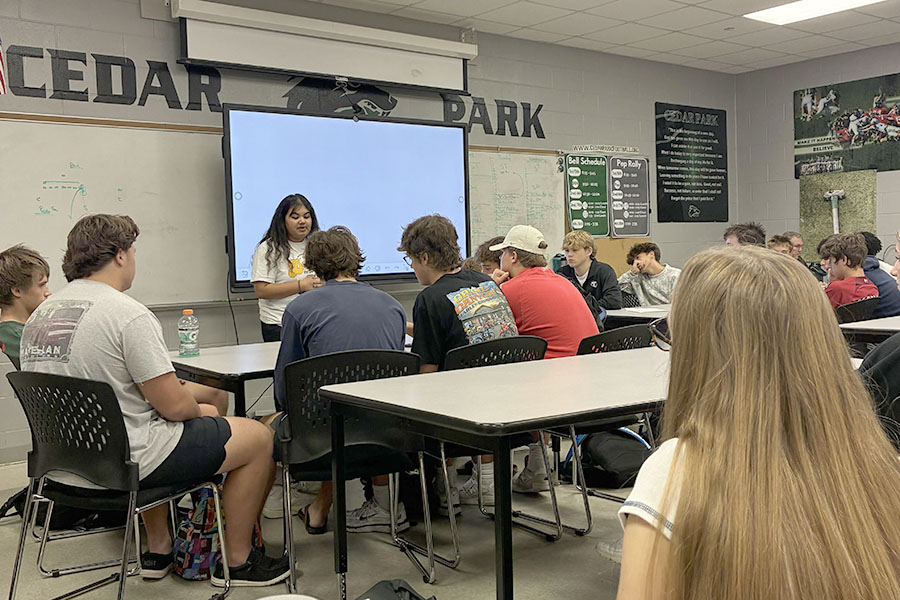

Actively engaging in a conversation with her students, AP English IV teacher Michelle Iskra teaches her students about the importance of reading multiple stories to get proper context. Iskra is one of the teachers who implemented an approach designed to prevent academic dishonesty, and said she believes everyone should work together to ensure an honest academic policy for students. “I think everyone [plays] a role in minimizing academic dishonesty,” Iskra said. “I’m very straightforward about it. But, I also give students many opportunities to show me what they can do, to be successful in their own way, and to work with other students collaboratively in terms of thinking and ideas, and then to prepare their own work.”

September 5, 2021

After a year of being online, students find themselves, once again, having to adjust to the academic environment of schooling. Getting up early, having to go to class in-person,and testing are just some of the things that students must adapt to.

During the pandemic, when the school was primarily functioning virtually, multiple reports from teachers regarding the use of specific programs like Quizlet and PhotoMath were prominent. The topic of testing in classes has now resurfaced the discussion of academic dishonesty among students.

The Math Department is no stranger to the use of such programs. Given the difficulty students face in those classes, the use of such programs are inevitable at times. Head of Math Department and Pre-Calculus and AP Calculus teacher Pam Martin is among those who said she saw an increase in academic dishonesty in her Pre-Calculus OnRamps class, specifically. She said a lot of her students had defaulted to the use of such programs to get ahead in their work.

“It is frustrating,” Martin said. “Frustrating to know that good kids, when they don’t know what to do, are going to default to PhotoMath. It’s so tempting, [so] I don’t blame them. We [had also] made all the tests open note, [so] we just gave up on that. So, things in the past that [we had] kids memorize, they didn’t even have to memorize.”

Martin added that the Math Department, at least, is working towards bridging the academic gaps that students have.

“All the way through our high school math courses, we know [that] kids are coming with gaps,” Martin said. “All of the different math teacher PLC’s are working really hard to try and patch those gaps. We’re talking to each other so we know what gaps there’s gonna be.”

Now that students are back in person, teachers are opting to change their classroom dynamics.

Some teachers are opting for a stress-free environment, such as Biology teacher Adam Babich, who feels the need to remove the feeling that students have to cheat.

“What I have seen, in my experience, is that people cheat because they feel like they have to,” Babich said. “They feel like there [is] very little room for making mistakes. And learning requires mistakes, especially in science. Not that the class is easy, [because] the material is hard [and] I want to challenge you, but I don’t want [students] to feel that if [they] make a mistake, that [their grades are] unsalvageable.”

However, others are opting for a more tight approach, one which stresses the importance of morality and moral consequences. This approach is also aimed towards anti-cheating, but one where it would be difficult to do so.

“Pretty much everything [that] I do in my course is designed to minimize cheating,” English IV AP Michelle Iskra said. “Ultimately, it is on the student. They have cheated themselves out of the educational experience. Sometimes, students don’t respect the courses they’re taking, and they’re doing it because other people are doing it, or they’re doing it because their parents have forced them to do it. That is a loss on the part of the student, and it’s dismaying for teachers.”

The cause of academic dishonesty is obvious to some teachers, such as Iskra, who blame it on the school system. Such teachers believe that the system is inviting students to resort to academic dishonesty in order to get ahead, such as the ranking system.

“In my experience, academic dishonesty has been about competition,” Iskra said. “ I attach it to the concept of the ranking system in high schools, which I despise. I feel like that is an incentive for students who would otherwise be well-behaved to do all kinds of things to get themselves into better positions, in terms of rank. In my experience, it has only been with advanced students. [It was like that] when I taught IB at Leander High School. There was an incentive to cheat, and I had to learn the hard way that I needed to create all of my own documents, and there were certain things that I could allow students to use that everyone was going to use and [a] whole lot of instances where I needed to create separate, unique assessment for each of my classes to keep that competition at a minimum.”

The discussion of academic dishonesty then brings up the question: What is considered academic dishonesty and what is not? Students are often taught to use their resources such as answer keys to check their work, or use online calculators to help them with problems. Teachers like English II Preap teacher Kimberly Vidrine often encourage students to use their resources.

“I often tell students, for example, when we’re reading a text, especially one that is a little bit of a reach, that I encourage them to use SparkNotes or what I call ‘cheat sites’,” Vidrine said. “Not in place of reading, but because when you do the reading, and then go back and check what those sites say because they are intended to supply people who didn’t read with a real clear understanding of the book, they offer a layer through which you can filter your layer of understanding. I consider that an appropriate use of resources as long as you did the work before you resorted to those sites.”

While what is considered academic dishonesty varies by course and department, the gist is ultimately the same: using the work of others.

“The Math department needs to know if [students] can demonstrate an algebraic process,” Martin said. “Or a proof process. Some sort of logical thinking. From Algebra I, solving multi-step equations, through quadratics and solving quadratics different ways, we are trying to see if [students] can logically think through and show us [they they] know what [they’re] doing.”

Since the Math Department expects this from students, academic dishonesty is pretty straightforward, according to Martin. She said academic dishonesty is utilizing the work of others.

“Academic dishonesty is using work that someone else created to show process,” Martin said. “It used to be leaning over and copying off your neighbor. Now, it’s copying work off of PhotoMath.”

Similarly, the English Department’s primary concern is making sure students give credit to the work of others, according to Iskra.

“We’re trying to make sure students give credit,” Iskra said. “That they don’t represent as their own ideas, someone else’s ideas. That includes parenthetical citations and using quotation marks. Sometimes, students don’t understand that paraphrasing ideas that don’t belong to them also need to be cited. Some of that is ignorance. Once I teach that concept, though, I expect students to be very respectful of it. I think sometimes students don’t understand that they’re misrepresenting their work, but sometimes it is intentional.”

That being said, teachers like Iskra are making it their goal to have students understand what is expected of them, and how to prevent the misrepresentation of their work. Part of that is giving students a chance.

“We teach it, we ensure students are clear about it,” Iskra said. “My colleagues and I probably are pretty uniform in our ideas about giving a student a chance, but if it happens again, then that [is considered] cheating.”

Teachers believe that working together to limit the extent of academic dishonesty is crucial. That this issue involves everyone, from staff to students. And by working together, they can help each other mitigate the effects of academic dishonesty, and help students get a better quality of education.

“I think everyone, students, teachers, administrators, school districts, we all play a role in minimizing academic dishonesty,” Iskra said. “I’m very straightforward about it. At the beginning of the year, I have in all of my syllabi, both my college students and for my AP students, a policy that is really clear. And I follow it. I’m fairly merciless when it comes to that. But I also give students many opportunities to show me what they can do, to be successful in their own way, and to work with other students collaboratively in terms of thinking and ideas, and then to prepare their own work. And to invest themselves in their own work. So, if I can get a student to know, or at least have faith, that they can figure something out, and they can do well and that if they don’t do well on the initial attempt, they can probably try again, then I can minimize that idea of possibly cheating.”

![Senior Jett Mckinney stores all the clothes in his own room, with half of it stored in his closet along with his personal clothes, and the rest taking up space in his room.

“There’s been times [when] there’s so much clothing stored here and it gets overwhelming, so I end up having to sleep somewhere else in the house,” Mckinney said.](https://cphswolfpack.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/DSC_0951-1200x800.jpg)

![Broadcast, yearbook and newspaper combined for 66 Interscholastic League Press Conference awards this year. Yearbook won 43, newspaper won 14 and broadcast took home nine. “I think [the ILPC awards] are a great way to give the kids some acknowledgement for all of their hard work,” newspaper and yearbook adviser Paige Hert said. “They typically spend the year covering everyone else’s big moments, so it’s really cool for them to be celebrated so many times and in so many different ways.”](https://cphswolfpack.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/edited-ILPC.jpg)

![Looking down at his racket, junior Hasun Nguyen hits the green tennis ball. Hasun has played tennis since he was 9 years old, and he is on the varsity team. "I feel like it’s not really appreciated in America as much, but [tennis] is a really competitive and mentally challenging sport,” Nguyen said. “I’m really level-headed and can keep my cool during a match, and that helps me play a bit better under pressure.” Photo by Kyra Cox](https://cphswolfpack.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/hasun.jpg)

![Bringing her arm over her head and taking a quick breath, junior Lauren Lucas swims the final laps of the 500 freestyle at the regionals swimming competition on date. Lucas broke the school’s 18-year-old record for the 500 freestyle at regionals and again at state with a time of 4:58.63. “I’d had my eye on that 500 record since my freshman year, so I was really excited to see if I could get it at regionals or districts,” Lucas said. “ State is always a really fun experience and medaling for the first time was really great. It was a very very tight race, [so] I was a bit surprised [that I medaled]. [There were] a lot of fast girls at the meet in general, [and] it was like a dogfight back and forth, back and forth.” Photo by Kaydence Wilkinson](https://cphswolfpack.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Kaydence-2.7-23-edit-2.jpg)

![As her hair blows in the wind, senior Brianna Grandow runs the varsity girls 5K at the cross country district meet last Thursday. Grandow finished fourth in the event and led the varsity girls to regionals with a third place placement as a team. “I’m very excited [to go to regionals],” Grandow said. “I’m excited to race in Corpus Christi, and we get to go to the beach, so that’s really awesome.” Photo by Addison Bruce](https://cphswolfpack.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/brianna.jpg)

![Actively engaging in a conversation with her students, AP English IV teacher Michelle Iskra teaches her students about the importance of reading multiple stories to get proper context. Iskra is one of the teachers who implemented an approach designed to prevent academic dishonesty, and said she believes everyone should work together to ensure an honest academic policy for students. “I think everyone [plays] a role in minimizing academic dishonesty,” Iskra said. “I’m very straightforward about it. But, I also give students many opportunities to show me what they can do, to be successful in their own way, and to work with other students collaboratively in terms of thinking and ideas, and then to prepare their own work.”](https://cphswolfpack.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/IMG_9078-900x675.jpg)

![Holding a microphone, baseball booster club president Chris Cuevas announces the beginning of the annual cornhole tournament. The event has been held for the past two years and is designed to raise money for the baseball program in a fun way. “We’re a baseball team, so people love to compete,” Cuevas said. “So we figured we better do something that gets [their] attention. They want to compete. It’s not a hard sport to do, and we have all different [skill] levels [of participants].” Photo by Henry Mueller](https://cphswolfpack.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/Henry-715-1200x900.jpg)